Have you ever thought about the dangers linked to dry fasting and how it connects to cancer? Let's explore how agents that cause mutations—things that can alter our DNA—play a role in this situation.

Dry fasting, where a person goes without eating and drinking, pushes the body into a condition where it starts to use its own reserves for fuel. This practice has been part of various cultural and religious traditions for centuries. Many people turn to dry fasting for potential health benefits, such as detoxification, weight loss, or spiritual reasons. While it can have different effects on the body, some of which are helpful, others might carry risks.

One important aspect to consider is the refeeding period—the time when you start eating and drinking again after a fast. This phase isn't just returning to normal; it's a unique state where the body is especially sensitive and certain activities are amplified.

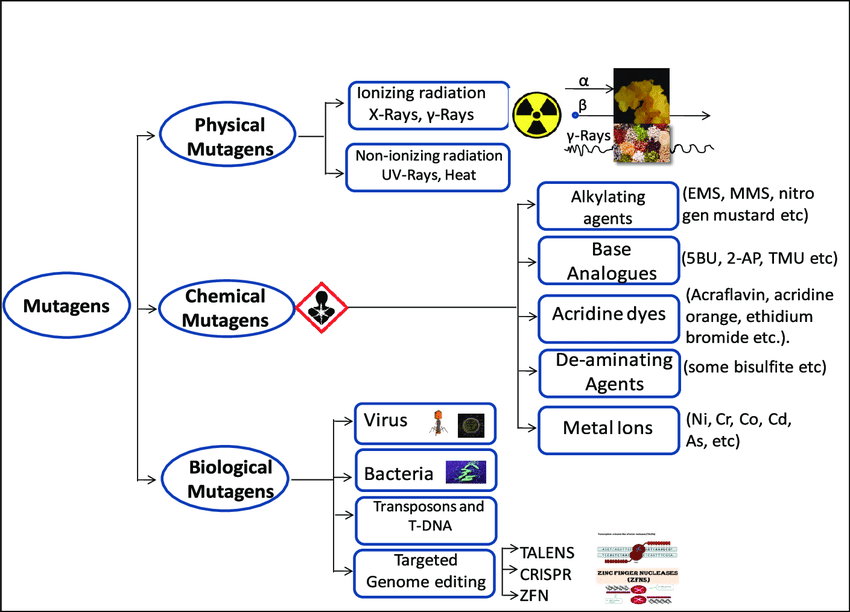

So, what exactly are mutagens?

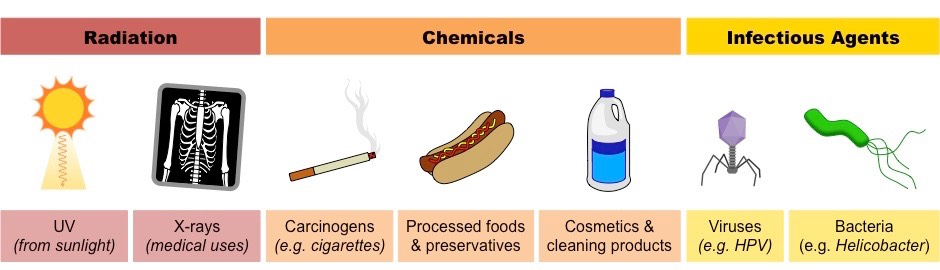

Mutagens are substances or factors that can cause changes or errors in the DNA sequence of cells. They can be physical, like ultraviolet radiation from the sun; chemical, like certain toxins in food or pollutants in the air; or biological, like some viruses that can integrate into our DNA.

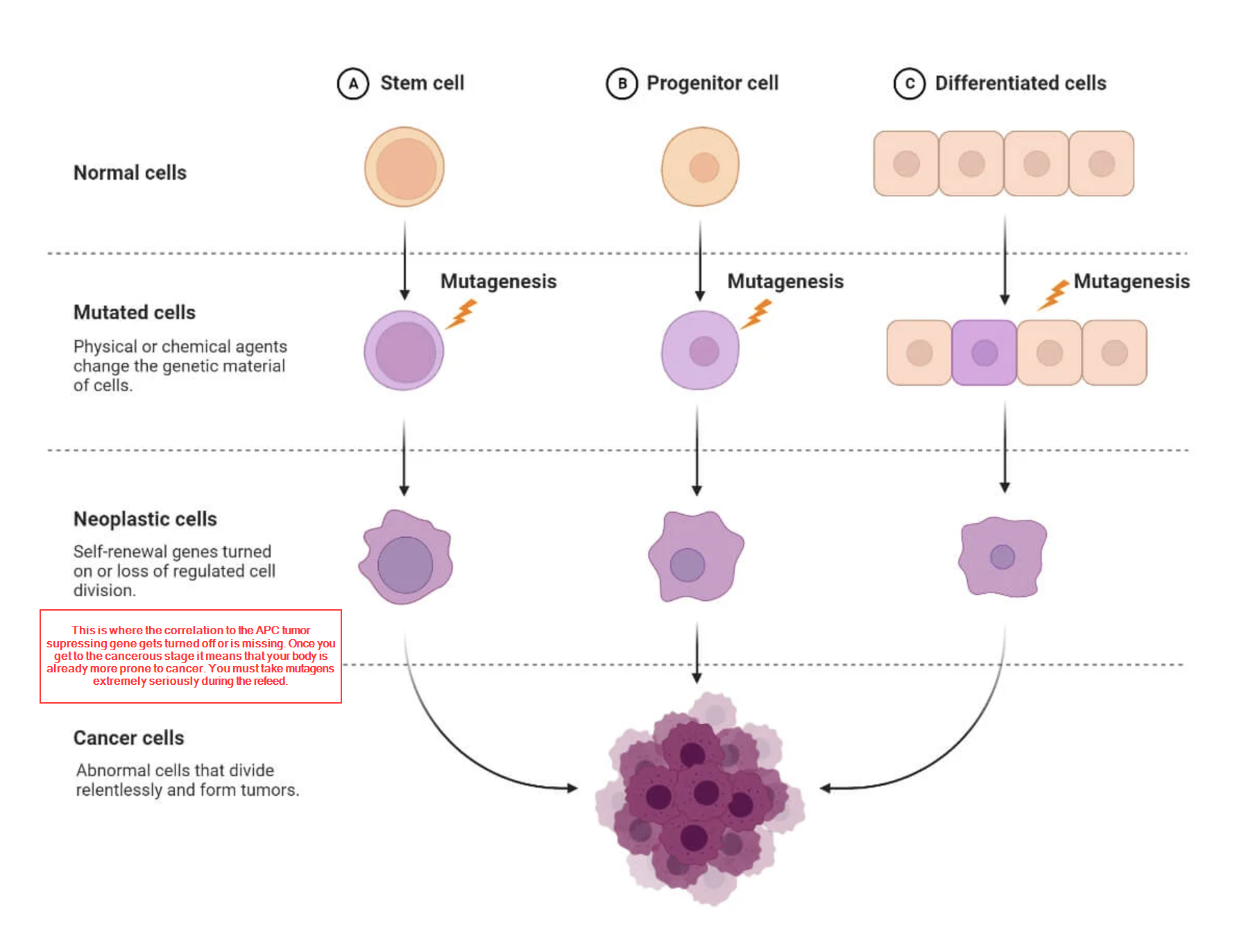

When our DNA gets altered, it can lead to mutations. While not all mutations are harmful—some are neutral, and a few can even be beneficial—certain mutations can disrupt normal cell functions. This disruption can cause cells to grow uncontrollably, which is how cancer starts. The body has mechanisms to repair DNA damage, but these systems can be overwhelmed or less effective, especially during periods of rapid cell division.

Moreover, the refeeding state is considered a third distinct body state, separate from the normal and fasting states. In the normal state, the body operates with a balance of nutrients and energy, maintaining stability. In the fasting state, the body shifts to conserve energy and use stored resources, such as glycogen and fat. Metabolic processes slow down, and the body may enter ketosis, burning fat for energy.

But in the refeeding state, the body is in a mode of rebuilding and replenishing. This rebuilding process involves a surge in metabolic activity, increased insulin production, and accelerated protein synthesis. The body is eager to repair tissues, restore energy stores, and normalize bodily functions. However, this also means that any mutagens present can have a more significant impact because cells are dividing more rapidly.

The refeeding phase can be a double-edged sword. On one hand, it's a time of healing and rejuvenation. On the other hand, if not managed carefully, it can lead to complications. One such complication is the refeeding syndrome, a potentially fatal condition caused by sudden shifts in fluids and electrolytes. This situation underscores the importance of reintroducing food and nutrients gradually and thoughtfully.

Therefore, it's crucial to be cautious about what we consume during the refeeding phase. Avoiding foods and substances that contain mutagens can help reduce the risk of introducing harmful agents into the body at a time when it's most vulnerable.

Study on Post-fast Refeeding cancer risk

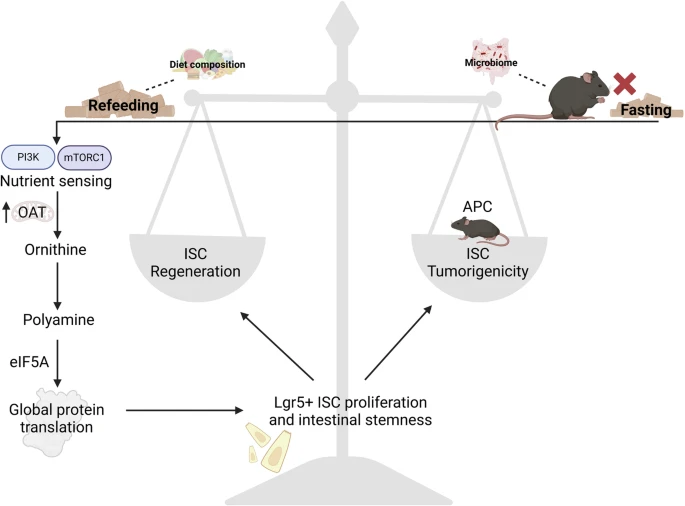

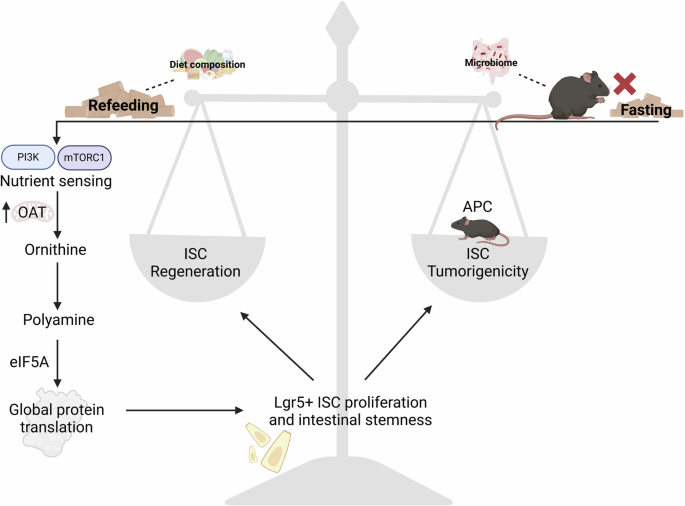

A recent study by Imada and colleagues, published in Nature, highlights this critical post-fast refeeding phase and its potential to both aid in regeneration and, under certain conditions, increase cancer risk.

Refeeding Is More Than a Simple Reset

During refeeding, intestinal stem cells (ISCs)—the powerhouse cells responsible for repairing and regenerating the intestinal lining—spring into action. These cells are among the most dynamic in the body, constantly dividing to keep the gut lining healthy. However, this flurry of activity is a double-edged sword. While it accelerates healing, it can also create a fertile ground for mutations, especially in the presence of certain genetic vulnerabilities.

In their study, researchers fasted mice for 24 hours, refed them, and observed a sharp uptick in ISC activity compared to mice that had uninterrupted access to food. They discovered that refeeding activated key nutrient-sensing pathways, specifically PI3K and mTORC1. These pathways are like switches that tell cells to ramp up energy production and protein synthesis.

One of the key players here is ornithine, a molecule involved in the creation of polyamines—compounds essential for building proteins and cellular structures. This surge in protein production is vital for generating new, specialized intestinal cells. But as exciting as this repair process sounds, it carries a catch.

High Division Rates: A Hidden Risk

The very quality that makes ISCs remarkable—their rapid division—also makes them prone to mistakes. Rapid cell turnover increases the likelihood of DNA errors, which, in the wrong conditions, can lead to precancerous changes. In mice with a genetic mutation that disables the tumor-suppressing APC gene, refeeding after fasting led to a noticeable rise in intestinal tumors.

This doesn’t mean fasting or refeeding directly causes cancer in everyone. It’s a specific combination of factors—like genetic predisposition and the metabolic environment during refeeding—that sets the stage. In the study, blocking the mTORC1 pathway helped reduce the tumor-promoting effects of refeeding, suggesting that fine-tuning these pathways might hold the key to safer fasting strategies.

Some common sources of mutagens

Let's take a look at some common sources of mutagens. It's important to understand what to avoid, especially during the refeeding state. For a lot of young and healthy individuals, the risk of mutagens is much lower, but I deal with a lot of cancer patients and I've heard of and seen enough horror stories linked to cancer worsening following a dry fast.

- Certain processed meats: Products like bacon, sausages, and hot dogs often contain preservatives such as nitrites and nitrates. These chemicals can form nitrosamines, which are potent mutagens, especially when meats are cooked at high temperatures.

- Overcooked or charred foods: Cooking methods like grilling or frying at high temperatures can produce compounds like heterocyclic amines (HCAs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). These substances are formed when amino acids and creatine react at high heat and are known to be mutagenic.

- Environmental pollutants: Exposure to chemicals like benzene, asbestos, and certain pesticides can introduce mutagens into the body. These substances can be found in industrial areas, contaminated water sources, or through the use of certain household products.

- Tobacco smoke and alcohol: Smoking introduces numerous mutagens directly into the lungs and bloodstream. Alcohol, especially when consumed in large amounts, can increase the body's absorption of other mutagens and can be metabolized into acetaldehyde, a known mutagen.

To minimize mTORC1 activation during the refeeding state and reduce cancer risks, focus on:

- Low-protein foods: Prioritize plant-based proteins like lentils, beans, or peas over animal proteins.

- Low-glycemic carbohydrates: Include foods like sweet potatoes, quinoa, and non-starchy vegetables to prevent insulin spikes.

- Healthy fats: Opt for avocado, olive oil, and nuts in moderation.

- Anti-inflammatory options: Incorporate berries, leafy greens, and turmeric for added protection.

What about milk kefir vs meat vs eggs in this sense?

Let's look at an example of "animal protein". I always advise that your main source of animal protein that still works in the refeeding window is milk kefir.

- Milk kefir: Lower mTORC1 activation due to its moderate protein content and probiotics, which support gut health.

- Meat: High mTORC1 activation because of its rich leucine and protein content, especially in red meat.

- Eggs: Moderate to high mTORC1 activation, as they are a complete protein with significant leucine levels.

Avoid high-protein and highly refined or sugary foods, as these can overstimulate mTORC1.

Some research suggests that antioxidants found in certain foods can help protect against mutagens. Antioxidants work by neutralizing free radicals—unstable molecules that can damage cells and DNA. Foods rich in vitamins C and E, as well as minerals like selenium and compounds like beta-carotene and lycopene, can help reduce oxidative stress on cells.

It's also beneficial to stay hydrated during refeeding. Water helps flush out toxins and supports overall bodily functions. While dry fasting involves abstaining from water, reintroducing fluids is essential during refeeding to aid in digestion, nutrient absorption, and detoxification.

Furthermore, being mindful of environmental exposures can help reduce the risk of mutagens. This includes:

- Avoiding secondhand smoke: Exposure to tobacco smoke can introduce numerous mutagens into the body.

- Limiting time in polluted areas: If possible, avoid areas with high levels of air pollution or industrial contaminants.

- Using natural products: Opt for cleaning and personal care products that are free from harsh chemicals and synthetic fragrances.

- Testing for radon: Radon gas is a natural radioactive gas that can accumulate in homes, especially basements. Long-term exposure can increase the risk of lung cancer.

Understanding the role of mutagens and how they interact with our bodies is essential for minimizing cancer risk, especially during vulnerable times like refeeding. The body's increased metabolic activity during this phase means that cells are dividing and DNA replication is happening at a faster rate. This accelerated activity provides more opportunities for mutagens to cause errors in DNA replication.

Moreover, the immune system can be temporarily suppressed during and after fasting, which might reduce its ability to detect and eliminate cells that have undergone harmful mutations. This suppression can further increase the risk of mutated cells proliferating.

In conclusion, dry fasting can have various effects on the body, and the refeeding phase is a critical time when the body is rebuilding and repairing. Being aware of mutagens and taking steps to avoid them during refeeding can help reduce the risk of cancer growth and support overall health.