The accepted scientific consensus is that while the skin contains aquaporins, which are channels that facilitate water transport, it does not significantly absorb water under normal or fasting conditions. The skin's primary function is to act as a barrier, protecting against water loss and external substances. This barrier is highly effective, and while minor water absorption can occur, it is not substantial enough to contribute meaningfully to overall hydration. The body's hydration needs are primarily met through oral intake of fluids. However, we're now going to dig into aquaporins and their relation to hydration in the body. In fact, they may be one of the keys to explaining the phenomenon of water absorption through the skin during prolonged dry fasting.

What are Aquaporins?

Aquaporins are a class of proteins that form water channels, playing a critical role in cellular water homeostasis. These integral membrane proteins facilitate the rapid and selective transport of water molecules across cell membranes, a process essential for numerous physiological functions in organisms. Each aquaporin is highly specific, allowing only water molecules to pass through, thus maintaining the delicate balance of water within cells and across tissues. Their discovery revolutionized our understanding of cellular water movement. Present in a wide range of organisms, from bacteria to humans, aquaporins are integral to various biological processes, including kidney filtration, plant hydration, and brain water regulation, making them a critical focus in both basic and applied biological research.

Aquaporin expression and water absorption through the skin

A Study, (Expression and function of aquaporins in human skin) found that up to 6 different AQPs (AQP1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 10) may be selectively expressed in various cells from human skin.

If we assume that dehydration plays a role in aquaporin expression, then it starts to make sense that the skin layer AQP levels will rise the longer we are in a dry fast, and the drier the skin.

And here we have evidence to support this. In this study: Dehydration-induced increase in aquaporin-2 protein abundance is blocked by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: they mention:

Such changes occur in response to chronic alterations in hydration, with water loading causing a decrease in AQP2 expression, while dehydration increases the AQP2 levels

This indicates that Yes, our body does upregulate and downregulate AQP's based on hydration status. So it becomes clear that there is a mechanism at play that may affect our water absorption capabilities.

So should you take baths or showers when on a long dry fast?

In considering the nuances of dry fasting, it's important to note some recent shifts in guidance from experts like Filonov. For over 20 years, Filonov advocated for cold plunges during dry fasting, believing in their benefits. However, he has recently revised this recommendation, now advising against them. His rationale is that exposure to water, particularly in the latter stages of a fast, can mentally challenge the faster. The body, upon contact with water, may enter a state of mild panic, intensifying cravings for water and making the mental aspect of continuing the fast more difficult. While physically refreshing, the mental fortitude required to persist becomes significantly tougher. Thus, he now suggests avoiding baths or cold plunges to mitigate this mental struggle. There is also the advice that your body will absorb water, and that you should not stay in water for too long. Hence why Filinov used to advise ice buckets over the head for a quick rinse instead of sitting in it.

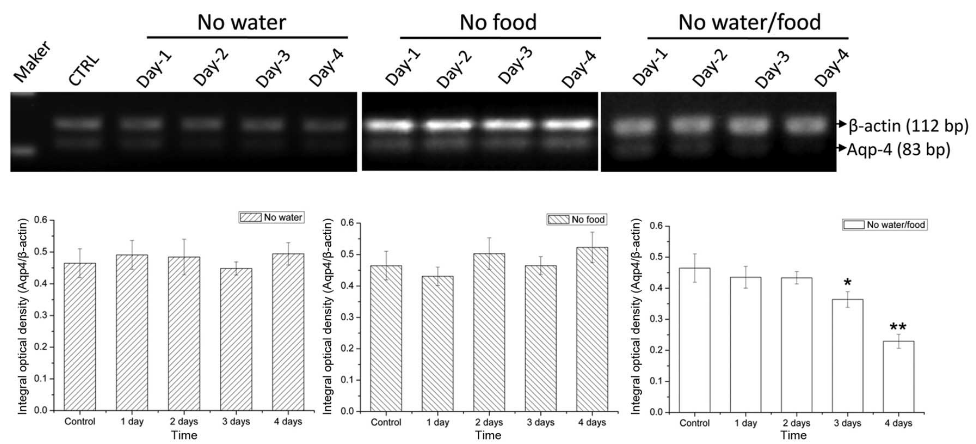

This change in approach aligns with studies on aquaporin activity during dry fasting, which show significant changes, especially in the brain, starting around the third day. This implies that for fasts shorter than 72 hours, activities like showering or cold plunges should not have a major impact. Even actions like brushing your teeth are considered negligible in their effect before crossing the three-day threshold. Post three days, however, caution is advised against introducing water into the mouth. This is due to a reduction in saliva production, which normally acts as a protective buffer against mouth acidity. Maintaining this protective coating on your teeth becomes essential in longer fasts, and avoiding water intake helps in this regard.

On a deeper level, if you possess the mental resilience to engage in cold plunges later into a fast, a brief, cold plunge is preferable over a warm shower or bath, which could potentially open pores and lead to greater water absorption. Ultimately, dry fasting is a personal journey, open to experimentation within safe boundaries. This information aims to guide your decisions, enhancing your understanding and helping you tailor the fasting experience to your individual needs and strengths.

How dry fasting affects brain water levels

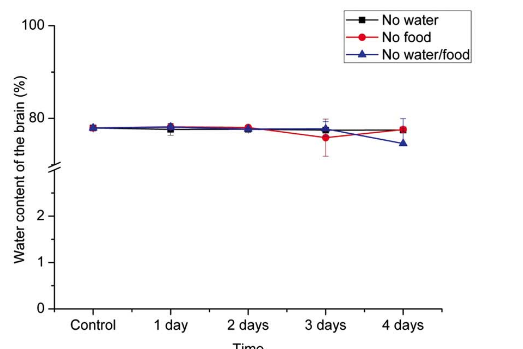

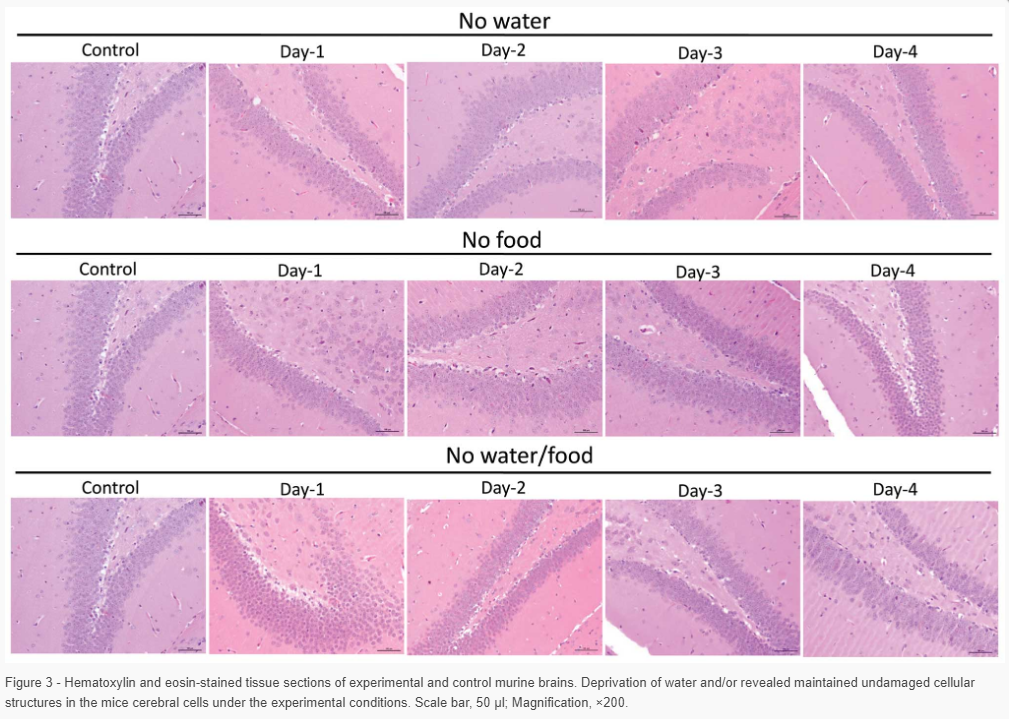

Because we’ve been shown that Brain Water Concentration remains stable during 4 days of dry fasting and regular water fasting, we know that there are water retention mechanisms at play. During a dry fast, right after the acidotic crisis, we see that AQP1 and AQP4 levels in the brain start to decrease. This indicates that the surrounding environment starts to lose water around days 3 and 4, but yet the brain tissues remain hydrated.

Since there are many anecdotal experiences of absorbing water during a very long dry fast, a possible mechanism that explains this would be the upregulation of AQP levels in the skin.

How to balance healing with dehydration levels on a dry fast?

Now that we understand there's a noticeable change in aquaporin levels in the brain around the third and fourth day of fasting, it begins to illustrate that these are the critical days when necessary autophagy and healing mechanisms are likely taking place. This is particularly relevant for those dealing with neurological issues, brain inflammation, or conditions related to autoimmune diseases, and possibly even depression. In such cases, longer fasts, like the 5-day dry fast outlined in The Scorch Protocol, might be necessary. However, it's important to recognize that a 5-day fast may not suffice for desired outcomes, leading to discussions about 7 to 9-day dry fasts as more effective for ultimate healing.

Nevertheless, it's crucial to balance safety with efficacy. I've analyzed this before, suggesting that the real intense healing for brain-related diseases starts from day three onwards. For instance, a 5-day dry fast equates to two days of intensive brain healing, whereas a 9-day fast would offer six days. To achieve six days of healing with 5-day fasts, you'd need to complete three separate fasts, totaling 15 days, compared to achieving similar results with a single 9-day fast. It's about assessing your situation, considering what you're willing to undertake, and how quickly you want to progress while maintaining safety.

Personally, I find the 5-day dry fast a safer option, but for those willing to push boundaries, longer fasts might stimulate more profound autophagy and brain healing as dehydration intensifies. Yet, the pivotal question remains: at what point do the risks outweigh the benefits? This is a delicate balance each individual must weigh, considering their health, goals, and what they're comfortable with in their fasting journey.