It's crucial to recognize August Dunning's significant contributions to popularizing dry fasting in North America and the English-speaking world. He is notably one of the first to 'westernize' this practice, which had previously been more prevalent in other regions, particularly Russia. While Filonov, another pioneer in dry fasting, introduced these concepts from Russia, his approach is somewhat limited by cultural and language barriers, and his retreats are located in settings unfamiliar to many Westerners. Filonov's style is more reminiscent of an old-school, strict discipline, contrasting with Dunning's empathetic and scientific approach.

My respect leans towards Dunning's method as it aligns more closely with my own. However, I acknowledge Filonov's extensive experience and the vast number of individuals he has assisted, providing him with a wealth of anecdotal and experimental data. In this article, I aim to encourage critical thinking and independent judgment, especially for those already exploring the unconventional path of dry fasting. It's easy to fall into the trap of blindly following authority figures, but part of taking charge of your health is learning to question and think for yourself.

You should understand that caring for your health is a personal responsibility. While guidance from experts can be invaluable, especially when navigating complex scientific concepts, it's important not to accept everything at face value. Be open to the possibility that even professionals can be wrong and that scientific understanding can change with new evidence.

This discussion is meant to provoke thought. Just because someone uses scientific terminology and understands the basics of processes like autophagy doesn't guarantee their complete accuracy. Trust your instincts, remain open to being wrong, and continue learning. Keep in mind that practices like dry fasting, despite their popularity, could still pose risks. Every day offers a chance for improvement and learning, a journey that should always be evolving.

"I count him braver who overcomes his desires than him who conquers his enemies; For the hardest victory is over self."

Fisetin

Fisetin is amazing, and biohacker gold. Dunning is unto something here, but if you put so much weight on fisetin you might as well get the whole NAD+ precursor supplement line.

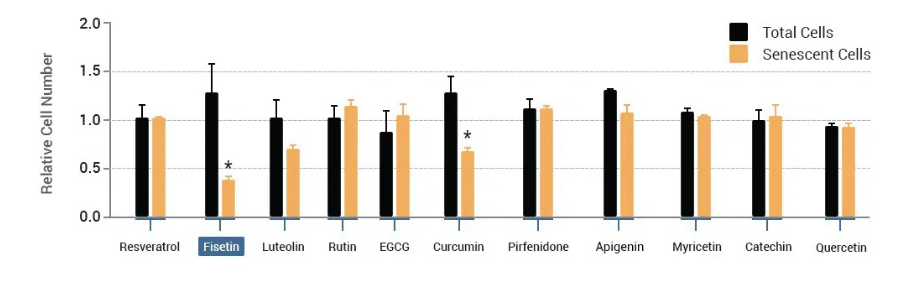

So why don't I agree with Dunning on how hard he pushes Fisetin? Well, he's trying to sell his supplement is one of the biggest arguments. You can find it in a lot of foods, and it's completely unnecessary in my opinion. What is the second strongest senolytic? Quercetin and Curcumin. Super cheap, and abundant. Get a liposomal version and you're golden. Sure if you're min-maxing hard, get fisetin - it's relatively safe and has ongoing studies. But it's expensive. Remember that lots of fresh fruits and vegetables contain fisetin. Maybe this is why a plant diet is more correlated with longevity than a meat diet (which contains little to no senolytics). Did you know coffee and green tea are very high in quercetin? And Milk thistle is not only good for the liver, but also a powerful senolytic. (for any of my readers suffering with autoimmune diseases, some senolytics can trigger allergy-type reactions, so you'll need to dry fast to heal those reactions first).

So why can you disregard fisetin? Because you have dry fasting - fisetin cannot touch the senolytic power of a dry fast. Save your money, and harness nature.

Baking Soda after a fast.

Unnecessary, and potentially dangerous due to edema and disrupting the body's natural bicarbonate production. In emergencies like extreme kidney pain, it can be on hand.

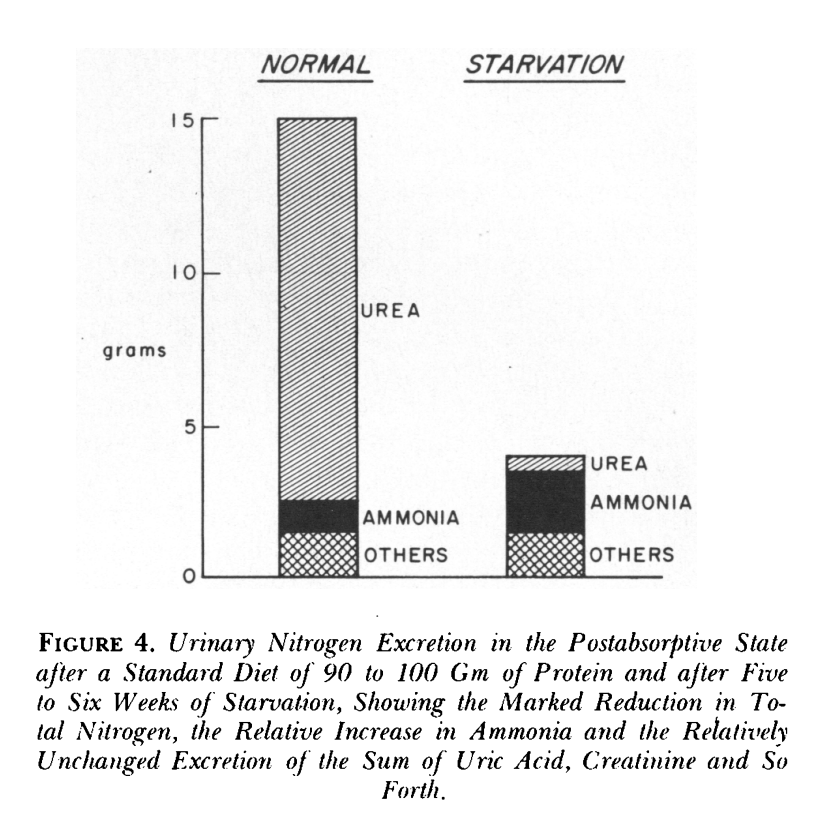

Let's talk about why we don't need to supplement baking soda right after a fast or even during one. It revolves around ammonia. If ammonia is removed through urine, it results in the formation of new bicarbonate to help maintain the acid-base balance. If it returns to the bloodstream, the liver processes it and consumes an equal amount of bicarbonate, essentially neutralizing the bicarbonate produced during kidney ammonia production.

This leads straight to the advice of NOT ingesting baking soda after a dry fast. I’ll give you a clue: Sodium Bicarbonate. The sodium molecule part of it prepares a big risk of edema. That means excessive water retention. Maybe you've already experienced it once or twice after a long dry fast. Your body bloats, and you're unable to get the excess water weight off. This is because the body holds on to sodium molecules and won't let go. The upregulated aldosterone of a dry fast inhibits natriuresis (sodium excretion), which means holding on to water. Give it a few days to stabilize first.

Not only is sodium not recommended too quickly after a dry fast, but our bodies produce acid daily as a result of breaking down proteins and fats. This is magnified a hundredfold during a dry fast. The kidneys use an amino acid called glutamine (from our muscles) to create ammonia and bicarbonate. Bicarbonate is then absorbed back into the bloodstream to help buffer acids, while ammonia can either be removed through urine or returned to the bloodstream.

This means that once we finish the fast, the production of fatty acids stops. So the body is now overcompensating with bicarbonate and is going into a hyper alkaline state. This study examined hypermetabolic alkalosis right after an 18-day water fast.

Can you imagine dumping excess bicarbonate into the body in this situation?

Sitting in the water - aquaporins

August Dunning discusses the practice of taking baths and swimming during a dry fast, essentially advocating for a 'soft' dry fast rather than a 'hard' dry fast. This approach, according to him, is primarily based on personal comfort rather than extensive scientific evidence. However, I have reservations about this method, especially regarding prolonged baths. Contrasting Dunning's view, Filonov recommends brief exposure to ice-cold water, which does not allow much time for water absorption but still offers a cooling, endorphin-like effect that may aid in continuing the fast.

This discussion brings in the element of mental fortitude. Immersing in water during a dry fast might make the experience mentally more challenging, even if it provides physical relief. It's somewhat akin to being in a kitchen filled with the aroma of delicious food while fasting, which some might find torturous.

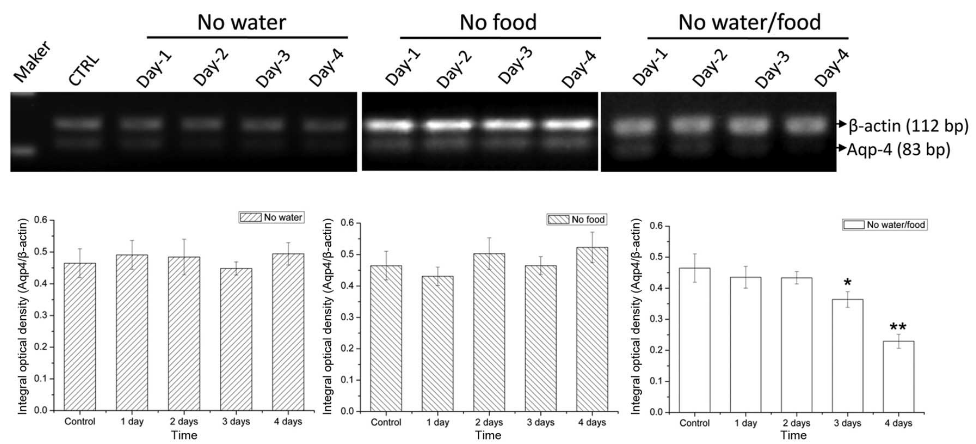

An important scientific aspect that Dunning might not have considered is the role of aquaporins. Aquaporins are a class of proteins that form channels in cell membranes, primarily for water transport, playing a key role in regulating cellular water balance. Around three days into a dry fast, aquaporin levels in the brain start to change, suggesting that the body might already be experiencing alterations in aquaporin activity, particularly in the skin. These proteins are known to be upregulated in response to dehydration. This is significant because, until the discovery of aquaporins, it was largely assumed that the skin does not absorb water to a substantial degree. However, this understanding is now being challenged. In cases of severe dehydration, our body might adapt to absorb significant amounts of water through the skin.

Understanding the role of aquaporins challenges some traditional beliefs about water absorption. If the body begins to absorb water through the skin in a dehydrated state, it could disrupt the intended mechanisms of a dry fast, as the body seeks to rehydrate and return to a state of normalcy. This discovery shows us how complex the human body is. Knowing this, it becomes quite obvious that if you want the full potency of a long dry fast, you want to avoid water exposure. But no matter what, you DEFINITELY want to avoid sitting in water for long periods of time during a dry fast.

Otherwise good. Not a hater. Thank you August for all the work you've done!